Stuff I Learned from Fairy Tales that I Really Need to Unlearn, Part 1: Finders Keepers

Goldilocks Leans In to the Small Porridge. Illustration by Walter Crane, 1873

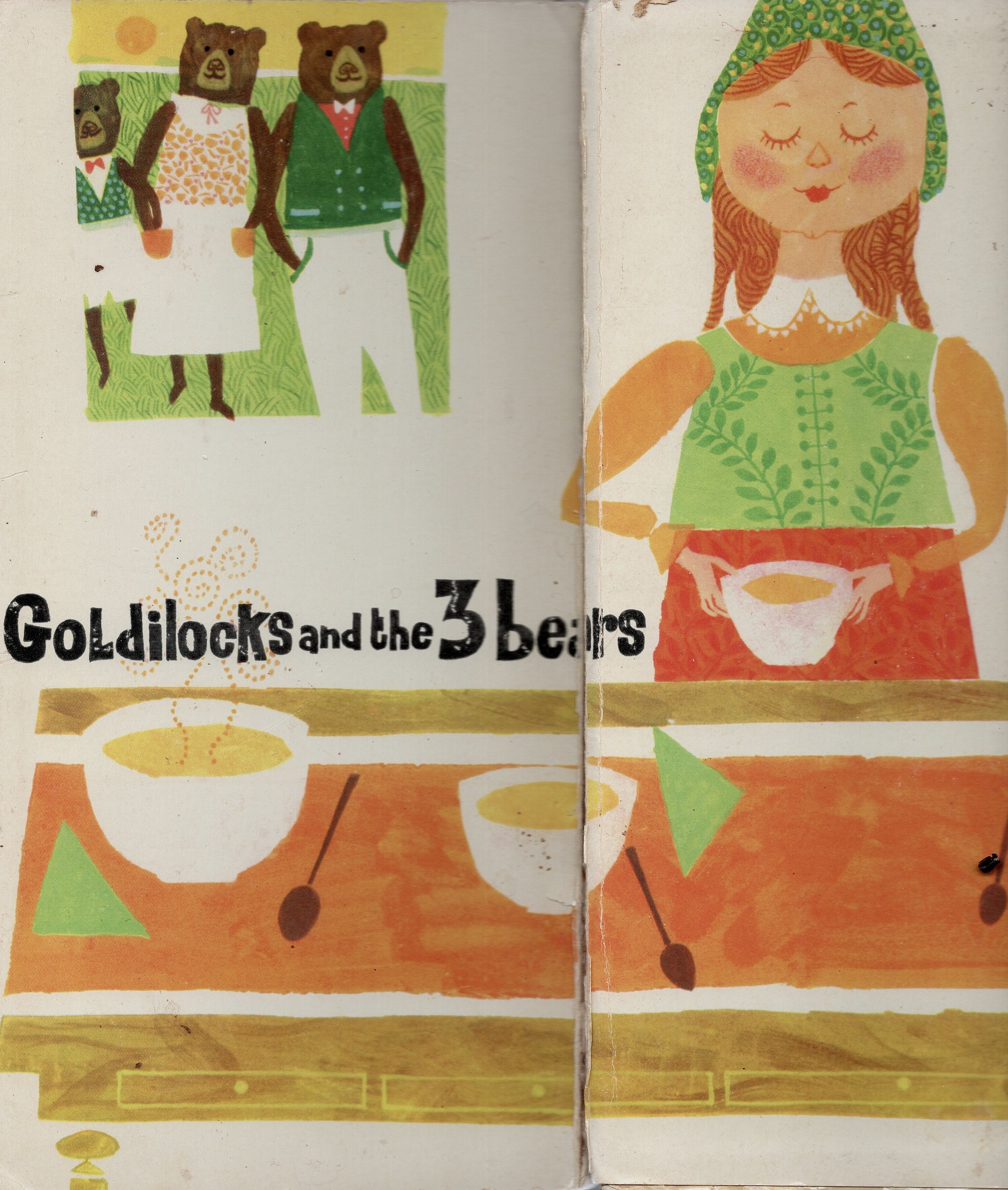

Recently I ran across a storybook from my childhood. I flipped through illustrations so deeply familiar that they seemed like dreams I’d had. My eyes rested on Goldilocks, preparing to sip at a bowl of porridge, and I noticed the returning Bear family framed in the doorway. They looked like a close family, wearing their Sunday best, their dark brown arms linked as they strolled. Suddenly this illustration seemed to be giving permission to a White child to take and use the possessions of a Black (Bear) family! How could I not have seen this before? How could it seem so normal?

The Bear Family Returns. Illustration by Lorraine Fox, “The Nursery Book,” 1960

Of course, it seems “normal" because it’s part of a cultural norm that I absorbed as a young child. (For more on early learnings of cultural norms see Stuff I Learned in Kindergarten That I Really Need To Unlearn). I started to wonder about stories I heard as a young child that are still told today, and that are part of our socialization into dominant cultural norms. I dove back into various dusty children’s story compilations I hadn't opened in years, and two cultural messages prominently emerged: “Finders Keepers!” and “Get to Work!” In this 2-part series I'll focus first on what we learn from Goldilocks and Jack & the Beanstalk.

Finders Keepers!

That Goldilocks illustration is also illustrating the norm that anything you find that seems ownerless or left behind, you can have and use. In Kindergarten I recall vividly the disappointment of seeing someone else playing with or using something I had been playing with minutes before, or something from home that I had misplaced. “Finders keepers, losers weepers,” came the sing-song retort when I asked for it back. The unmistakable meaning was “Too bad. Get over it.” And I never recall my teachers intervening in this. To be fair to them, in an elementary school setting most things belong to the classroom and not to the individual child, so allowing this taking and taunting may have been their way of enforcing communal ownership.

But beyond the classroom it had the opposite effect. Rather than making me think that most things are “ours” I became acutely aware of which things were or could be “Mine!” And this mindset that if someone isn’t “using” something it’s up for grabs has deep roots and dire consequences in Western society. The roots of it go all the way back to edicts called papal bulls issued by Pope Alexander IV in the 1400’s. These asserted the rights of the Christian nations of Europe to colonize, enslave and plunder native peoples and lands, casting explorers and conquistadors as the “finders keepers.” On the flipside, they asserted that indigenous people or "infidels" had only a “native right of occupancy,” with no claim to the land, dehumanizing them and relegating them to the “losers weepers” role. These ideas supported the expansion of the United States from east to west coast, as well as into various American “territories” such as Puerto Rico or Guam. They continue to be used as precedent in the US legal system into this century, where they are referred to as the Doctrine of Discovery. For a concise overview of this policy check out Shawnee-Lenape attorney Steve Newcomb’s talk.

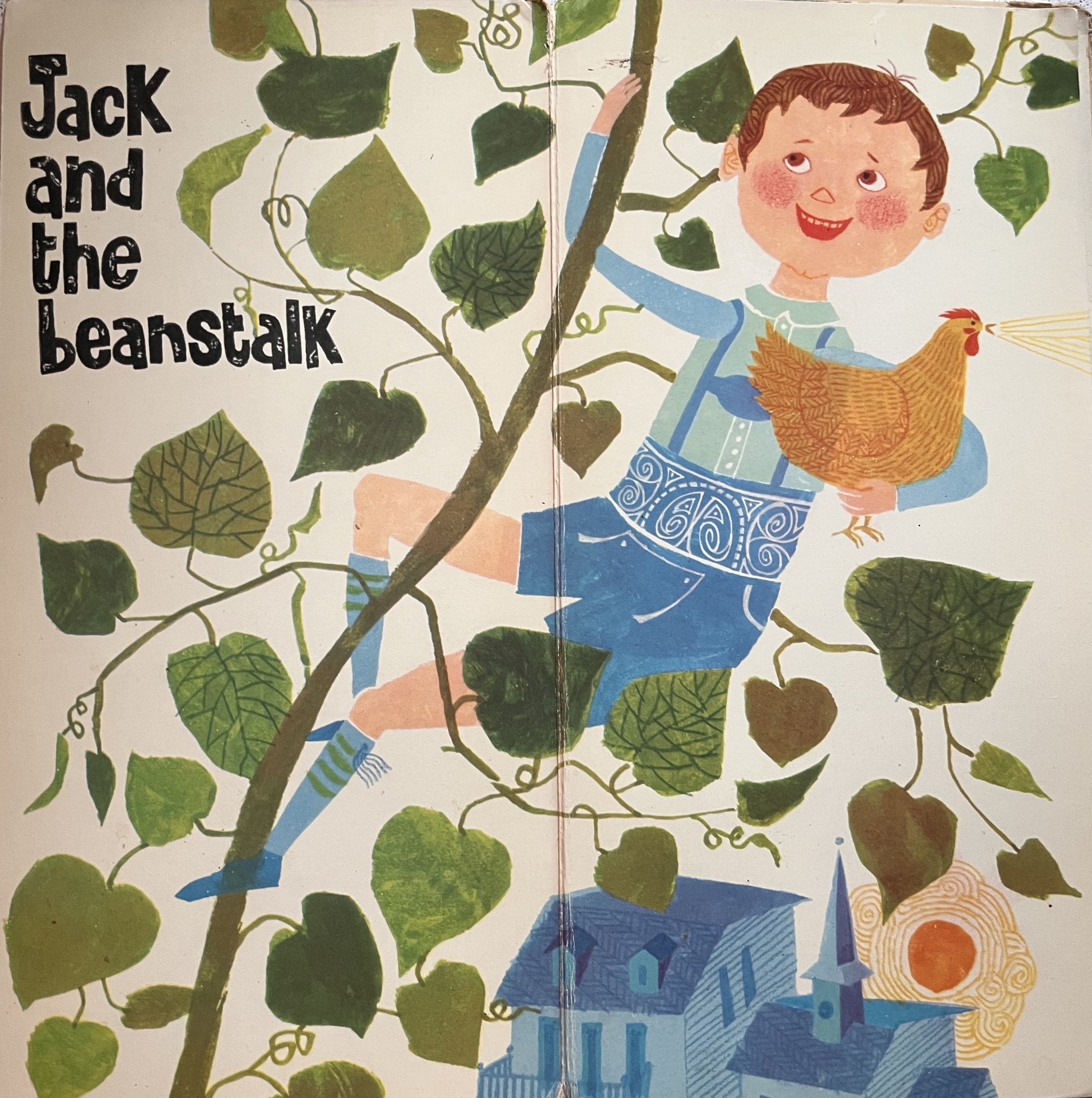

Jack Returns With the Booty. Illustration by Lorraine Fox, “The Nursery Book,” 1960

The fairy tale that best illustrates this behavior has to be Jack and the Beanstalk. Confronted with a magical beanstalk the size of a giant sequoia tree, the young protagonist climbs up it and “discovers” a new land occupied by a Giant and his Wife. The Giant is xenophobically hungry: “Fee Fie Foe Fum, I smell the blood of an Englishman,” he sings. Notice that it’s assumed that the occupant of this new land is particularly hostile to people from Jack’s country of origin. Jack takes this as his cue to plunder some gold and bring it home - after all the Giant wasn’t “using” it or perhaps wasn’t putting it to as good a use as Jack and his impoverished mother would. Each time Jack and his family deplete a looted resource, Jack heads back up to giant-land and steals something else. And his greed extends from financial gain to cultural appropriation as he takes a magic harp. When the Giant finally hears Jack making off with his harp, he follows him; so Jack chops down the beanstalk, ensuring that the Giant will fall to his death while not killing him directly.

As a child, I was caught up in the menacing nature of the Giant. He’s huge and hungry and it’s clear that he eats little boys he finds in his own land. I celebrated Jack’s ingenuity in escaping, and was proud of him for helping out his mom. And of course, Jack couldn’t let the enormous cannibal follow him home! The message I took was that Jack had every right to take the gold, the golden-egg-laying goose (or hen) and the magic harp because he was the better person. As a cannibal, the Giant was clearly an infidel, so less human than Jack and his English neighbors. He didn’t deserve those nice things.

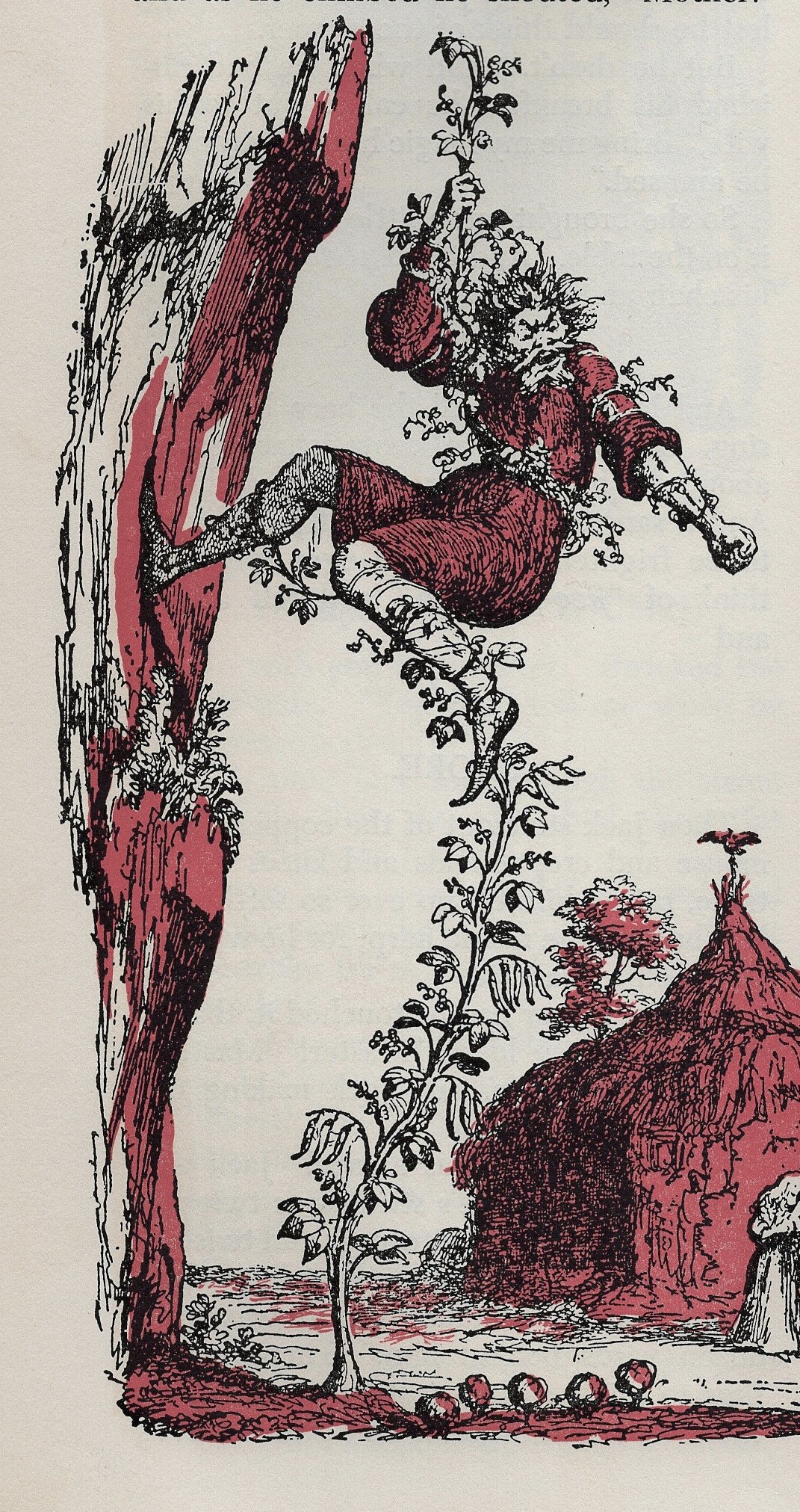

Aggression or Righteous Anger? Illustration by George Cruikshank, 1854

But on closer examination, the giant had no track record of crossing into Jack’s home country for his hunting, cannibalistic or otherwise. For all intents and purposes, he’s minding his own business until the young foreigner enters his land and begins plundering his stuff. And when he finally begins to defend himself, he’s killed in a way that makes him seem like he was the aggressor all along.

All of this has sickening echoes of colonial attitudes and practices – even the sequence of plundering resources to appropriating culture. Historically, Native Americans have been cast as aggressors any time they have pushed back on colonizing White settlements, including the “Dakota war” in my state of Minnesota. The same can be said for the framing of the Haitian revolution, which put fear of Black uprising in the hearts of enslavers throughout the Americas. And, while the US government wasn’t afraid to get its army involved in directly putting down “uprisings,” there have also been policies that engineered Native deaths in an indirect way, such as sanctioning killing of bison herds or distributing smallpox-infected blankets. Nowadays, most of us settler descendants are no longer in the business of land theft. But White musicians have repurposed the magic harp of Black music since minstrelsy, and the fashion world is rife with “tribal” designs applied with no compensation to their cultural owners - a “Finders Keepers” with a less obvious “Losers Weepers” of lost potential revenue.

Storybook Learning:

Anything that I “discover” is mine to keep; other people’s loss is not mine to worry about.

Consequence:

I’m unable to see “ownership” of intellectual or physical property unless it is in active use by an individual. This leads me to appropriate things out of convenience or greed, or just because they’re cool. It doesn’t occur to me to credit or compensate owners who are absent or who themselves share community ownership.

Unlearning tip:

When you become aware of something new - be it a lost wallet, an artwork, a spiritual practice, or a style of dress - take a moment to pause and appreciate it. Then ask: Where did it come from? Who does it impact if you use it? Are there layers of meaning you don’t yet understand?

Goldilocks: A Heartbreaking Epilogue

This week a grownup modern day Goldilocks has demonstrated that the echoes of Finders Keepers are still wreaking havoc. This White Goldilocks found and kept an iPad that her neighbor children (a Black family) left nearby. When one of the children brought his mom with him to ask for it back, Goldilocks cast them as the frightening Black Bear family returning. As Jack did with the Giant, she saw them as aggressive rather than assertive, and killed the mother. Unlike Jack she did this directly and immediately, shooting through her still-closed front door. And unlike the Bear family, the wee little one was a human boy, who was standing next to his Mama when she was shot.

The state of Florida, where Goldilocks and her neighbor family live, has a “Stand Your Ground” law. This type of law enshrines the process of projecting one’s own aggression onto others by allowing anyone who feels threatened on their property to use deadly force against a perceived aggressor. This is the grownup equivalent of the Kindergarten accusation, “He started it!” Both function as an all-purpose deflection of blame and an excuse to escalate a fight.

And, the fairytale connection here is not far-fetched. The legal doctrine that Stand Your Ground laws are based on is known as the “Castle Doctrine.” It allows us all to fantasize that our home is our castle, deserving of its own alligator-filled moat and armed sentries. So is our car, and in the most extreme versions, our immediate personal space. The Castle Doctrine relieves us of our duty to retreat from whatever barbarians are at the gate.

This fantasy may be ridiculous, but it is also real. And its seeds are sown when our young minds are open and ready for ideas to take root. Clearly my next research needs to be into stories that teach us to love the idea of castles.

If you want to be sure not to miss the rest of the series, subscribe below to get my articles directly in your in-box.