Cloudy with a Chance of Woke: Weathering Our Changing Language

Photo credit: Rie Gilsdorf

“language changes, just like cloud patterns change. It has never not changed, and you just can’t stop it.”

— Professor John McWhorter, Columbia University

Last month I wrote about how to be more welcoming in antiracist spaces. Rather than ambushing people who choose outdated words in the shifting landscape of language, we could patiently bring them up to date. In an effort to practice what I preach, this month I’ll answer some questions I’ve heard lately from white people newer to equity-focused spaces.

I heard my city described as “Majority Minority” the other day — what does that even mean?

Photo credit: Rie Gilsdorf

The term “Majority Minority” certainly is confusing. For starters, it’s an oxymoron, a phrase whose two parts are opposites, like “jumbo shrimp.” But there’s another layer that can add to the confusion for each of the component words. Both majority and minority refer to the demographic rank of a group compared to others in a particular place. And, because of the different patterns of settlement, immigration, and internal migration in the USA, a group that is in the majority in one region can be in the minority in another. For instance, the population of Minnesota at the last census was 76% White, 6% Hispanic or Latino, so if you live in that state and are Latino, you’re in the minority. By contrast, your brother who lives in California would be part of the 40% majority there, with White residents in the minority at 35%. That’s relatively straightforward – unless you live in the City of St. Paul, where White folks make up the largest single group, weighing in at just under 49%. That means the remaining 51% is made up of various smaller groups, making the city “majority minority.” Another way of thinking about this is that any time no one group has at least 50% of the population, you have a “majority minority” situation.

What makes the term “minority" problematic is that in the US it has long been used to refer to people whose census category is not White. So, when people use it in that sense in greater Minnesota, it can be a statement of fact; but when people say “minority” to refer to folks other than White in California, it is no longer accurate.

Speaking of Majorities, who are the “People of the Global Majority?”

Photo credit: Rie Gilsdorf

As a short answer: this is another way to refer to people whose census category is not White. Remember that majority and minority are comparative demographic terms that are place-based. In North America and Europe, a White majority has been thought of as the norm . Yet globally, White people have always been in the minority, with current estimates being approximately 12-16% of world population. The idea of “People of the Global Majority” is to zoom out past the small context of a particular region and take into account the demographic rank of people whose census category is not White in the entire world’s population.

There are several reasons people use this term. “Majority” carries with it a sense of power in numbers, while “minority” has a less powerful connotation. After all, people in the majority set the cultural norms that produce a sense of belonging. Alluding to the “global majority" flips that script for people whose census category is not White, reminding everyone that there are plenty of places where the default leadership is not White, and plenty of leadership potential in any group. Depending on who you ask, It either ignores or transcends the historical obstacles whose fallout various groups continue to deal with (take “redlining” real estate segregation policies for example), instead painting an asset picture of people of color. Either way, it builds solidarity among various peoples once colonized by European settlers.

See also POC, BIPOC, and Black, Indigenous and racialized from my earlier post.

What is “White Saviorism” and why does it matter?

Photo credit: Rie Gilsdorf

The term “White Saviorism” describes a paternalistic style of involvement of White people in communities of color, one that presumes the White people know best how to fix the problems of the global majority. The name may make you think of North American missionary groups doing charitable work among the poor of the global south, but it is also applied to other philanthropic organizations working in any community of color. It has now been generalized to apply to individuals that hold this attitude.

Often White people will show up in the White Savior mentality early on in their journey of racial consciousness. They realize that inequalities exist, and they want to help out. Often people in this phase feel the pressure of Action Bias and jump right into action without taking the time to ask the people they want to help what is really needed. This can range from sending pork products to Muslim communities or flour to people who have the gear and recipes to cook with rice, to pulling older children away from sibling care responsibilities in order to participate in programming. However positive the intentions, and however resourced the plans, they come off as presumptuous or arrogant.

The idea that external structures can simply be plunked down and function well in a different environment has not fared well. Alternative approaches such as Theory U, Appreciative Inquiry and Human Centered Design all start from the idea of self-determined change using the assets already present in the community. As a facilitator of change efforts it makes sense to me to build on existing strengths in the daunting process of creating substantive change. And, on a personal level, when I receive suggestions or help that starts from a positive view of me and my community, I’m far more receptive to the ideas, and to forming a relationship that goes beyond a single transaction.

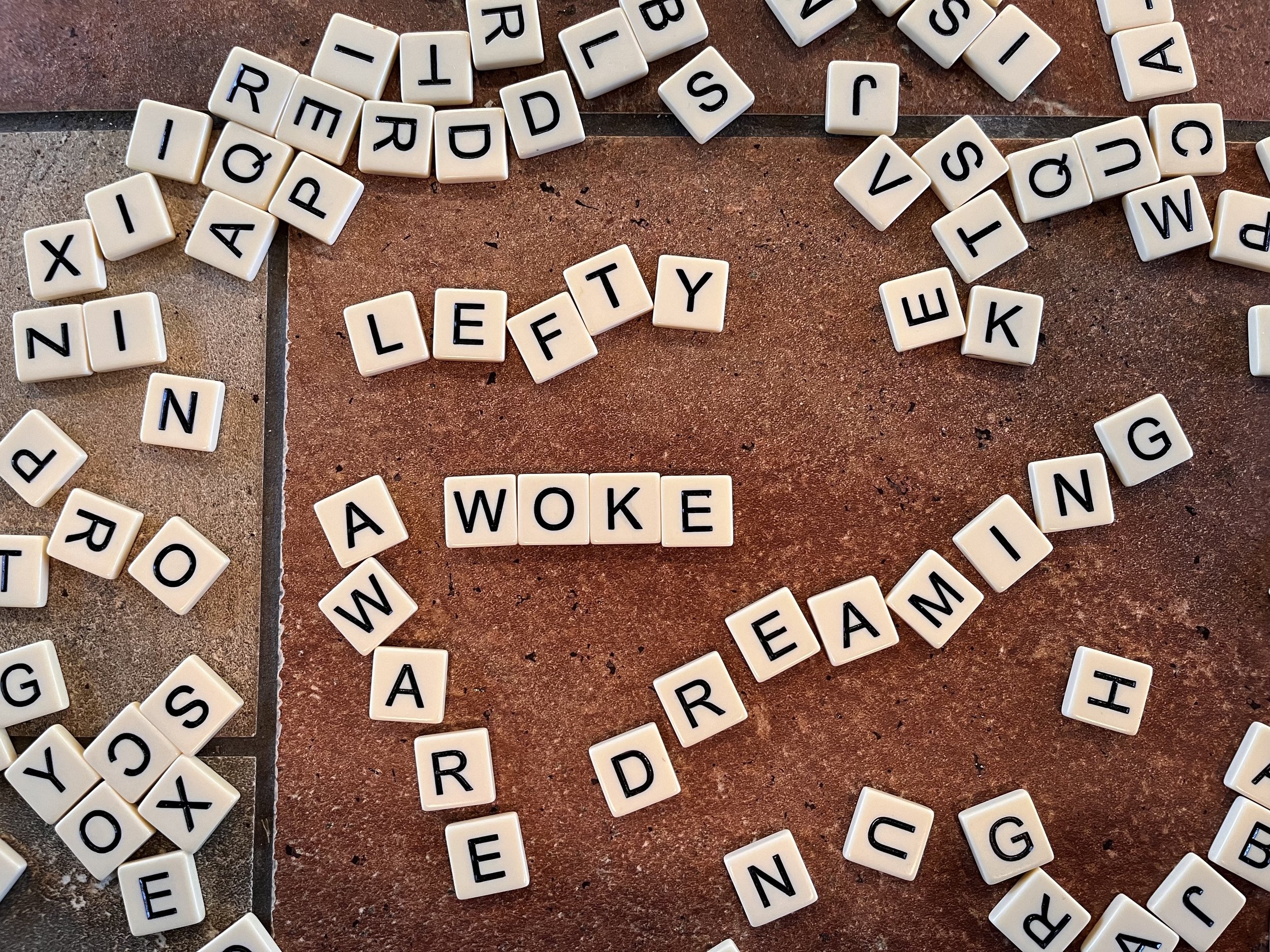

Is “Woke” a new term? Suddenly it’s all over the place.

Photo credit: Rie Gilsdorf

I wrote in my earlier language article about marginalized groups repurposing old terms that had been slurs, as with “queer.” “Woke,” by contrast, is an old term that recently has been repurposed by powerful people on the far right. Used in Black communities and labor movements as far back as the 1920's, “woke” was coined to express active alertness to systemic oppression. It wasn’t to “Be woke,” but to "Stay woke," not a state but a process. It also connotes that sense that once you’ve become conscious of the way the system works, you can’t unsee it.

It's recently been used as a slur by right wing officials to ridicule progressive policies as insincere or performative political correctness. There’s a sense on the right that the left is always changing the rules, as a “gotcha.” This lends itself to reconstructing “woke” as a thing to fear: “the woke mob,” coming to get you, or your children and . . . embarrass them? The Florida Stop WOKE act (currently under injunction) and similar laws in other states target any consciousness-raising or historical teachings that could make anyone feel “guilty or distressed.” This colorblind approach may seem even-handed, until we examine who potentially feels distressed by this history, and who takes on real stress within the status quo.

“the Dream rests on our backs, the bedding made from our bodies.”

— Ta-Nehisi Coates. Between the world and me

What’s the alternative to staying “woke?” Sleepwalking comes to mind - a state of activity while asleep and unaware of one’s surroundings. Author Ta-Nehisi Coates in Between the World and Me, writes of White Americans as “Dreamers,” blissfully unaware of their impact and seeing no need for any substantive change. By contrast he graphically describes the daily distress of Black Americans as one that keeps them from sleeping: “the Dream rests on our backs, the bedding made from our bodies.”

This is, of course, a distressingly frank way to put it. But here’s where awareness of the “White Savior'' mentality can help. Staying in White Saviorism causes White folks to look at the entire system as one giant problem that’s ours to solve. It’s overwhelming and tempts us to numb ourselves out by looking away, throwing ourselves into the issue of the day, and insulating ourselves from anything that would cause us to awaken from the pleasant dream that everything is just fine as it is. Ditching the White Savior mentality allows White people to inquire what’s needed currently, and then work in community to take a step, reflect, and take the next. This avoids the grandiosity that leads to overwhelm, and produces a feeling of agency that dispels distress. Small steps, taken consistently, allow everyone to learn what works, course-correcting along the way. In the long run they are more productive than occasional massive but flawed projects.

Language is Like Clouds

In my earlier language post I highlighted the advice of linguist John McWhorter,: “Language changes, just like cloud patterns change. It has never not changed, and you just can’t stop it.” I used this to illustrate the futility of wishing for a set glossary of approved terminology. This month, flowing from ideas of the “welcoming committee,” it strikes me that keeping the metaphor of cloud patterns in mind gives me more patience when people turn up with antiquated words. It could be that the last time they looked, the weather was different. Or it could be that they’ve just woken up. I’d rather present them with a warm cup of coffee and a conversation than a cold glass of water in the face. That way, they’re less likely to fear waking up at all.

“keeping the metaphor of cloud patterns in mind gives me more patience when people turn up with antiquated words.”

Do you wish you could have more patience with language fumbles — yours or other people’s?

Have you come across any terms that you’d like to understand better?

Are you hearing questions that you’d love some context to help you answer?

Let me know, I’d love to have that coffee and conversation.